Spit, 41x51cm, oil on canvas, 2020

Fold, 41x51cm, oil on canvas, 2020

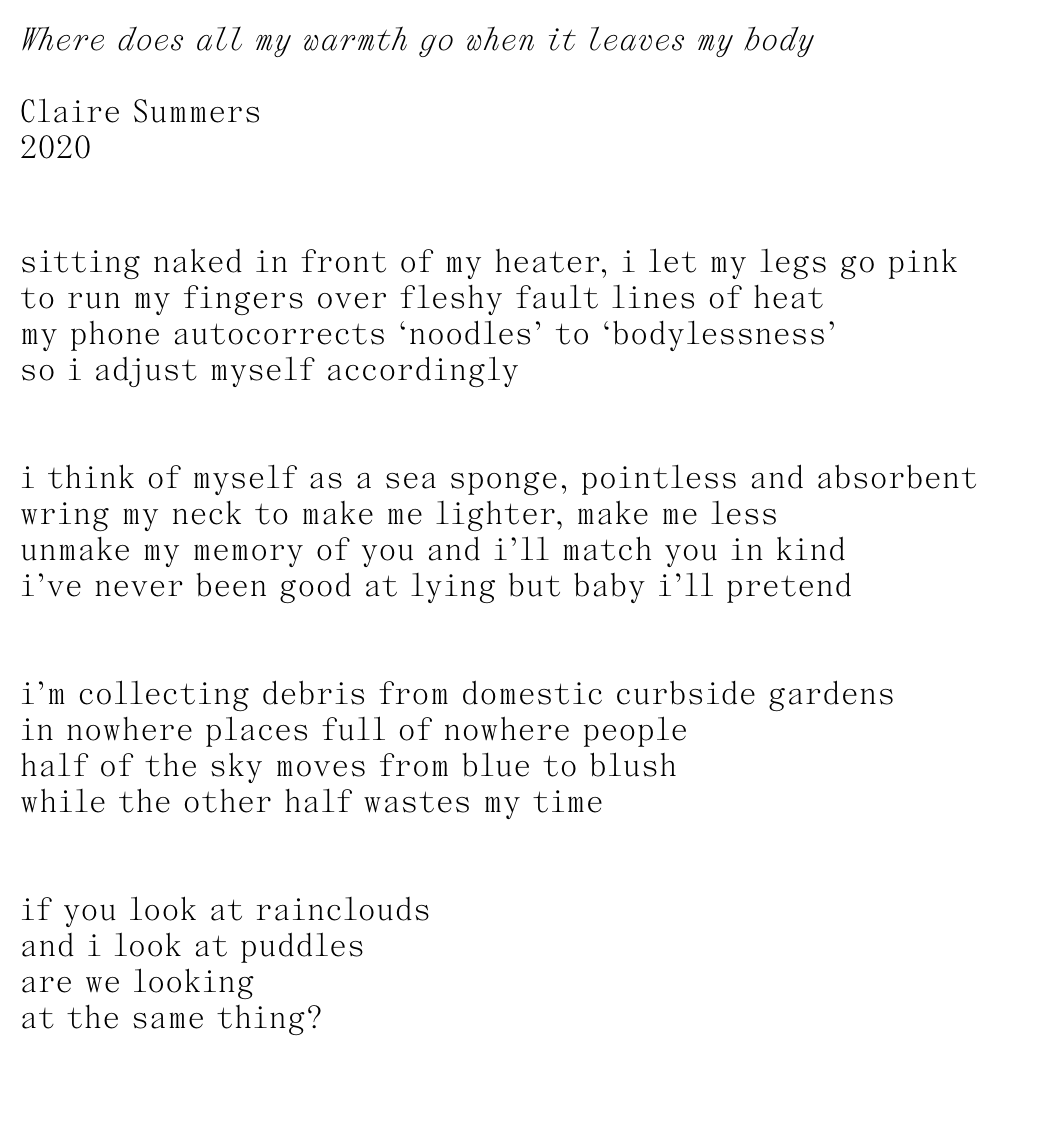

Cry Baby, 41x51cm, oil on canvas, 2020

Gut Gloss, 90x120cm, oil on canvas, 2020

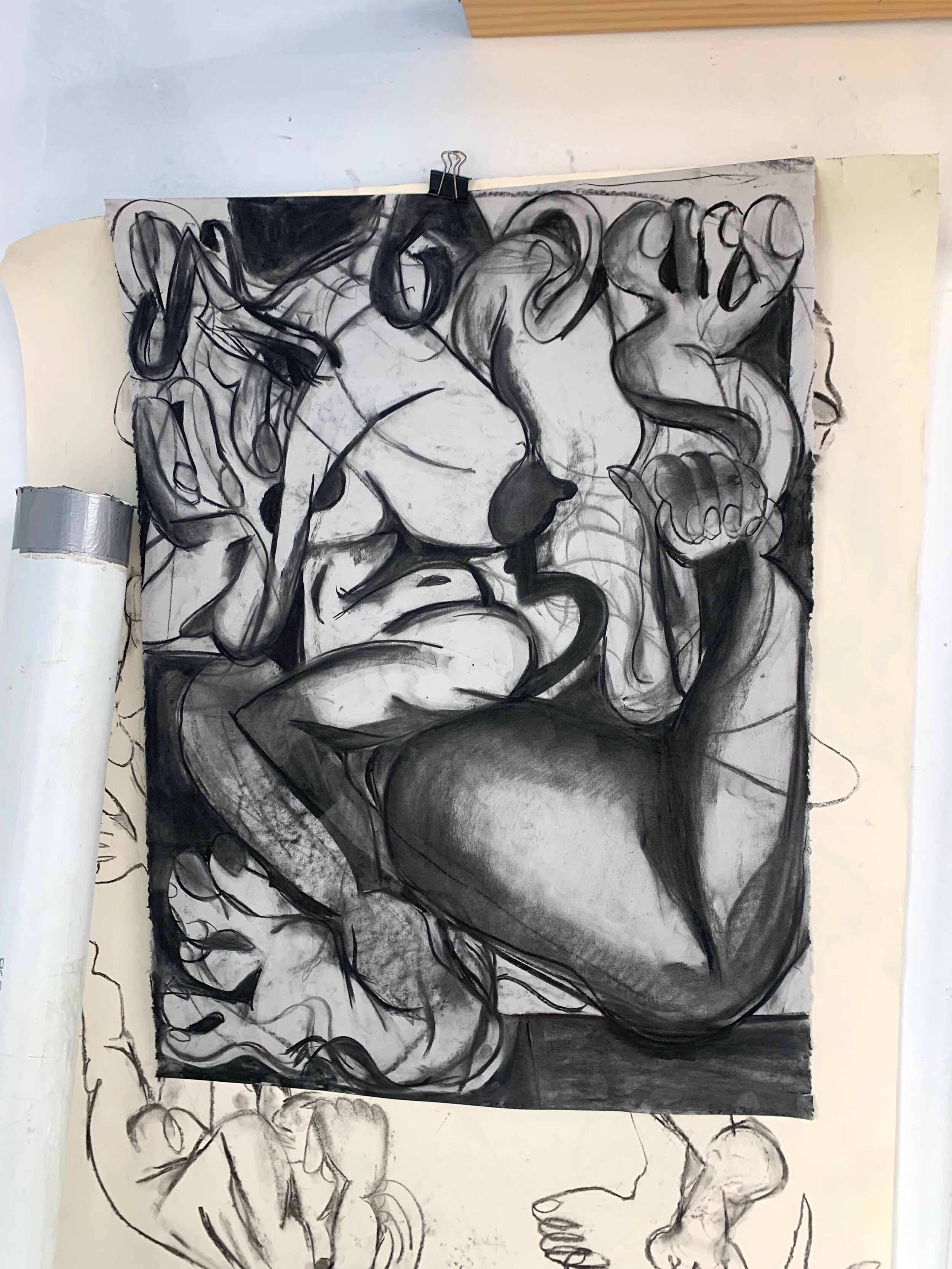

Untitled ,

Claire Summers

2020

The internet is a giant room, and you’re alone in it. Everyone who has ever plugged in has passed through the room and left something for you to find. The most precious thing I have ever found in the room is Cecil Robert. I know Cecil as an avatar, a sun-tanning, book-reading furry lazing under a blue and red

umbrella. They are the guardian of a YouTube channel, a cyberspace treasure chest of songs that have been manipulated and mutated to give them what is a holy kind of sentimental significance. Cecil edits songs – Leonard Cohen’s poem-cum-ballad Suzanne or Molly Nilsson’s celestial Hey Moon! - to sound

like they’re coming from another room, from a concert you’re not at or from the eerie interior in a deserted shopping mall.

Each song is given a sense of place, a setting instantly understood by our commonplace memory of its tactile décor. Cruising this catalogue of edits, the act of listening morphs into something physical. One sense provides the structure for another. Only a few shifts in a song’s frequency in either direction create the distance, the muffle, the reverb that puts a wall between you and the imagined person who you’re listening to it with. You are rendered a spectator, a secondary participant, one among the throng. It’s submergence in a strange experience of emotional osmosis.

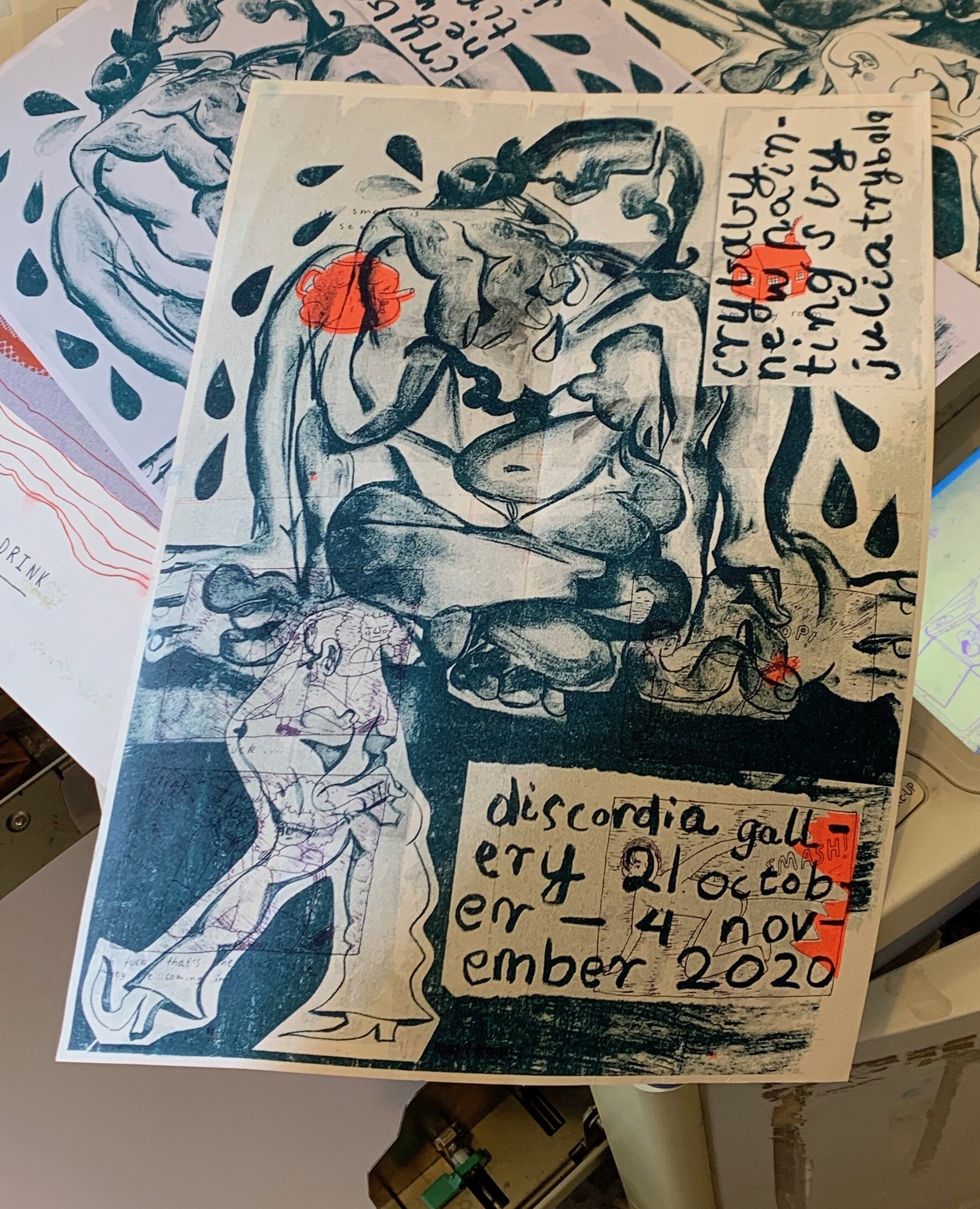

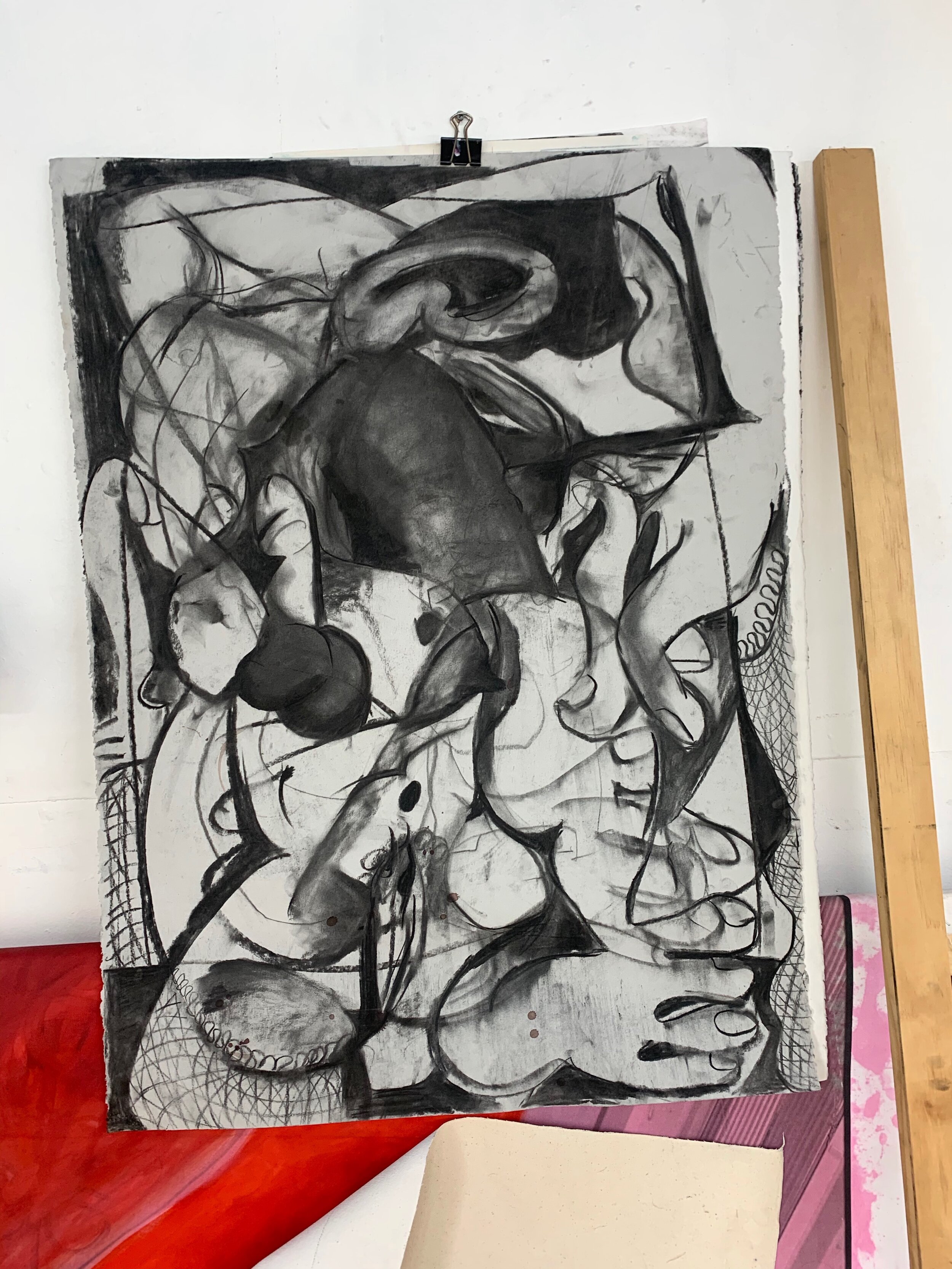

Cry baby offers the same landscape of relatability, the same haunting proximity to a feeling that was not, at first, yours. Julia Trybala’s new paintings for DISCORDIA are instinctively auto-biographical: cramped self-portraits that feel at once icky and intimate. The viewer meanders over a terrain of soft, squishy skin – deep, bruised purples and vivid, blushing pinks feel like the cheeks at full flush or a rush of blood in the body – before the eye locks to the gaze of our protagonist. In a manner that edges to the precipice of unnerving, each figure peers back at you, mirror-like. No longer is the work the ‘other’, separate from you, but an echo of your own vulnerability. The story and its sentiment become shared, just as with the song seeping from another room.

Again, one sense lends itself to another. ‘To look’ becomes a carnal sensation, perceived not only by the eye but by the body entire. Each painting has its own distinct physicality, tracing the lines of a sometimes- indistinguishable number of tangled figures; hunched, fleshy forms folded in on one another in an exchange where nudity is an afterthought. The exposure of the body is an act of becoming, where revealing the ‘self’ is simply a way to retain it. Here, the body is the resting place of an exhausted longing, and of a shyness that feels sacred. Tears, dribble and sweat are gooey accents among the many creases

and crevices, small motifs that tell of the grotty mess of unashamed solitude

These works, the product of Trybala’s practised rotational routine, were created with urgency from the same space of yearning we have collectively been suspended in. If we find ourselves already in the aftermath, the new mode of normality, do we recognise it as a nothingness or a somethingness? What happens when nothing happens is that you experience loss, the discomfort of staying the same, the spectacle of dying one day at a time. Trybala’s paintings from this time are a rebuttal to the nothingness, an acknowledgement that our loneliness, our enduring stasis, is its own something. Despite the implication of the title, nothing of our cry baby feels wussy or weak. Rather, tenderness and fragility are harnessed as an expression of resolute defiance.

Trybala’s figures, her distorted vision of her own body and her own self, feel like something private, a secret told to only you. The temptation – when someone shares themselves with you, reveals their secrets – is to confirm your empathy by offering tales of your own knowledge of that feeling, that experience. And while these paintings feel like they belong to more than the cry baby inside each frame, there is something to be said for seeing yourself in them while holding reverence for the distance between the boundaries of their skin and the boundary of yours. Bite your tongue, press your back against the wall, slide down to the floor and listen quietly to the song being played on the other side

Text, poem and photography by Claire Summers